By Anitha Quintin

Disclaimer: The statements, thoughts, and information presented in this article are those of the author, Anitha Quintin, and interviewee, Mr. Jinwoo Park, and do not represent the May 18 Memorial Foundation or its research programs, the U.S. Department of State or its Fulbright Program. The interview was originally conducted in Korean, and all translations are done by the author.

Following its independence in 1945 and until 1995, South Korea received nearly $13 billion in foreign aid. Since then, the Asian Tiger has established itself as a “global development co-operation partner,” finding a seat on the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) Development Assistance Committee, alongside the world’s largest providers of aid. According to the OECD, Korea primarily directs its aid to other Asian countries, including frequent humanitarian assistance such as its recent contribution of $900,000 to a U.N.-led humanitarian aid initiative for Myanmar. Like other global leaders, Korea views its commitment to the preservation of human rights as a core principle. Yet Korea’s support of others fighting for democracy is not a mere political matter; it is a historical and cultural one as well. As the Ministry of Foreign Affairs explains: “as a country that has achieved economic development, democratization, and improvement in human rights within a span of one generation, the Republic of Korea aims to contribute to the international human rights agenda based on its national experience.” But what exactly is the Korean “national experience” that forms the basis for Korea’s foreign contributions? One key part is the May 18 (5.18) Movement, an important event in the South Korean struggle for democracy.

The 5.18 Movement

On the morning of May 18, 1980, student protesters gathered at the gates of Chonnam National University (전남대학교) in Gwangju, standing in opposition to the Chun Doo-Hwan military regime, which had seized power the previous day in a coup d’état. Paratroopers stood guard on the other side of the fence. By May 19, protests had grown in size and moved to downtown Gwangju, and General Chun Doo-Hwan sent in the 11th Special Warfare Brigade. Over the following two days, the military resorted to increasingly violent methods of suppressing the more than 10,000 protesters. On May 21, they opened fire.

Civilian militias scrambled to arm themselves and began pushing the military back. Citizens declared Gwangju a liberated city by May 24, but three days later 20,000 troops re-entered the city and defeated all civilian militias to retake control of the Provincial Government Office.

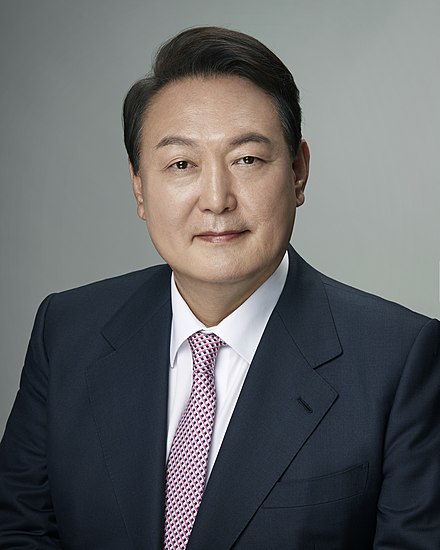

One cannot discuss democracy in Korea without acknowledging the role of the May 18 Movement and subsequent civilian massacre by the military regime. Now, there are annual memorial events, with even President Yoon Suk-Yeol paying tribute to the protestors—an unusual move for conservative presidents, who generally tend to express more ambiguous views of past Korean dictators like Chun Doo-Hwan. Yet Jinwoo Park, Director of Research at the May 18 Memorial Foundation, explained that these acts of remembrance were not always commonplace: the first commemorative event occurred in 1997. Before then, the military government interfered with the bereaved families’ attempts to hold memorial services.

After the end of the military regime in 1987, those who denied the 5.18 Movement were mostly relegated to fringe political parties. Despite its fringe nature, misinformation about the May 18 Movement continues, particularly affecting victims who are now compensated through monetary assistance and social services. On occasion, they face accusations of lying and continuing their advocacy for reasons of “economic interest.”

It is precisely due to this contested memory that the work of organizations such as the May 18 Memorial Foundation—which has programs dedicated to archiving of the May 18 Movement’s history and to the promotion of democratic values—remains essential. Despite now enjoying a strong democracy, Korea—and Gwangju especially—knows just how difficult it is to cultivate peace domestically. Within a generation, the Korean people not only had to fight against an oppressive dictatorship, but also against forces trying to erase this history.

5.18 and Global Democracy

“Myanmar’s pain is Gwangju’s pain. Hong Kong’s pain is not just Hong Kong’s pain, it is 5.18’s pain.” —Jinwoo Park

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre in Gwangju, civilians organized to help each other, recognizing the importance of the collective. One of the most emblematic images of citizen mobilization during this time—and the first Park noted when describing the events following May 18—is that of blood drives. As hospitals were overwhelmed by the number of casualties, citizens lined up to donate their blood despite the risk of being killed by the military on their way to or from the hospitals. Additionally, residents cooked and distributed meals and shared motor vehicles in an effort to circumnavigate state provided resources. This sudden and rapid mobilization, which Park described as nothing short of “a miracle of 5.18,” has left a lasting impact on Gwangju’s collective psyche.

The experience of surviving hardship—together— motivates Gwangju’s consistent support for those in need both domestically and abroad, whether it be in the form of blood drives, food donations, or monetary support. “When COVID first hit Korea in 2020 and the Daegu region was severely impacted,” he continued, “Gwangju citizens were among the first to provide support.” May 18 advocacy groups in Gwangju also expressed their support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests in 2019, according to a Hankyoreh report. There are also currently biweekly meetings of support for Myanmar’s civilians in Gwangju, and a group called Myanmar & Gwangju Solidarity sent approximately $46,000 to groups affiliated with Myanmar’s democratic movement in 2021.

Gwangju, its history marred by violence and oppression, cannot help but see a reflection of its pain in others’ fight for democracy. This is why the May 18 Memorial Foundation continues to advocate for peace and democracy across the globe through programs such as the Gwangju Democracy Forum and the Gwangju Prize for Human Rights—an award granted to those “who have contributed significantly to the development of human rights, unification, solidarity, and peace of mankind.” As a member of the Korean Civil Society Association (한국시민사회단체), the Foundation also works to petition the Korean government. For instance, it recently cosigned a letter by the Korean Civil Society Association regarding the 2022 ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus Experts Working Group; since the meeting invited representatives from Russia and the Myanmar Junta, the Foundation called for the Korean government to boycott the event.

Further acknowledging the importance of Gwangju and its 5.18-related organizations in the fight for democracy and freedom, the Asian Human Rights Commission announced the Asian Declarations on a right to justice, also known as the “Gwangju Declarations.” These declarations help draw attention to gaps in the justice processes of certain Asian countries; though they address the failures to protect human rights in the present day, the choice to announce the declarations in Gwangju and the heavy discussion of May 18 during deliberations indicate its continued influence on human rights.

While Gwangju remains the epicenter, memorial events for the 5.18 Movement occur around the country–it was, after all, the fate of the entire nation that shifted as a result of the movement. Similarly, other pivotal events led to Korean democratization, such as the April Revolution—which overthrew the Syngman Rhee dictatorship in 1960—and the June Democratic Struggle in 1987—which led to the establishment of the current Korean government. Korea’s commitment to supporting democracy abroad is in accordance with similar initiatives from other democratic leaders. However, Korea’s protracted and only recently concluded fight for the establishment of a democratic government—in which 5.18 was an integral part—makes it particularly attuned to similar struggles abroad. When Gwangju helps people advocate for democratic reforms, it is extending aid to the Gwangju of 1980. It is ensuring that others do not have to suffer alone as Gwangju did. And as long as there are still people fighting for democracy, the memory of 5.18 will continue to influence Korean foreign policy.

About the Author

Anitha Quintin is currently a Fulbright Scholar teaching at Hwasun High School in Jeollanam-do, South Korea, and a volunteer research assistant at the May 18 Memorial Foundation in Gwangju, South Korea. She is a 2021 UW-Madison graduate with majors in Mathematics, Political Science, and International Studies. Anitha’s research interests include the role of youth in contentious politics, the influence of colonial legacies on modern international relations, and U.S. foreign policy to East Asia and the Sahara-Sahel region.